Why are pro-environmental attitudes more common among the privileged? In a new article in The British Journal of Sociology, [free access version] I challenge three common explanations and propose a fourth: that strong ecological views among those rich in cultural capital reflect a form of symbolic asceticism—a moralized distancing from wealth and materialism. Rather than a new ecological habitus, these views represent an adaptation of older class distinctions to a context where environmentalism has become individualized and moralized.

Read on if you want to know more:

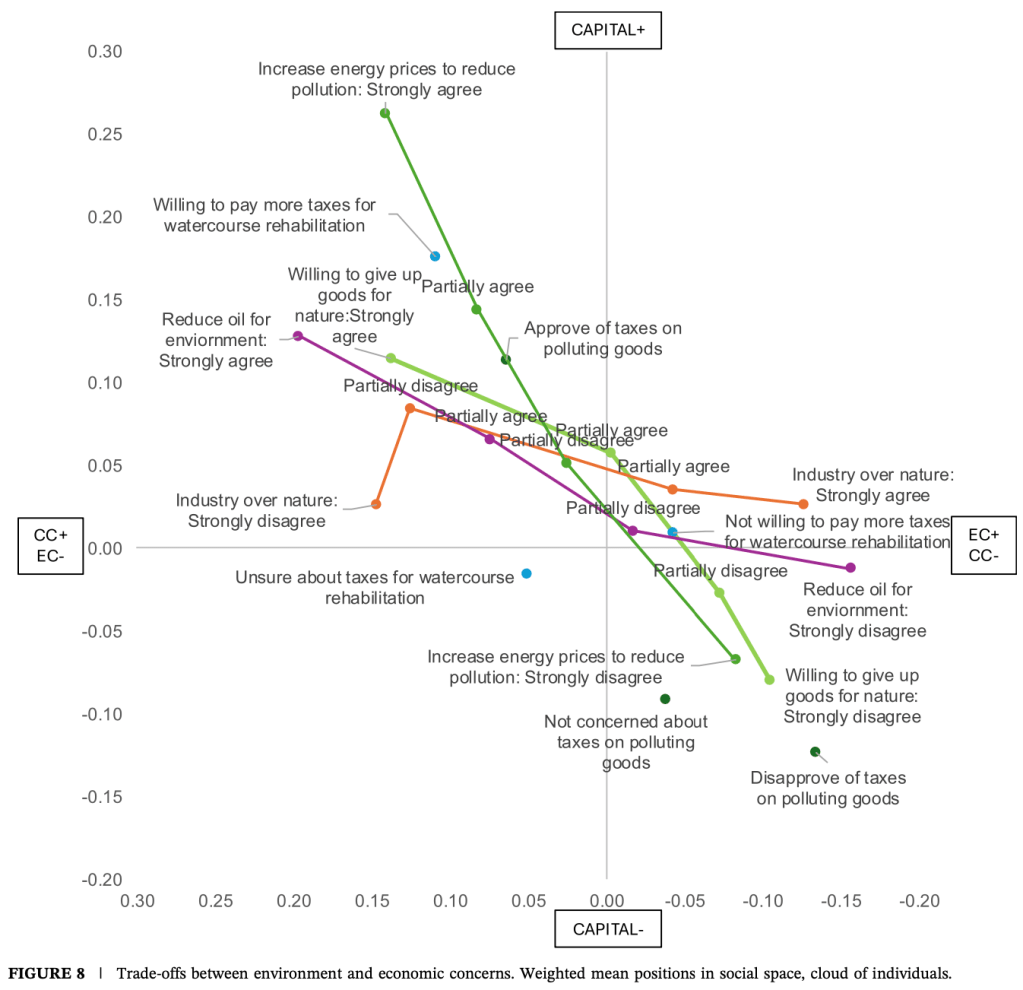

It’s long been observed that people with more resources—education, income, social standing—are more likely to express concern for the environment. But why is that? In my recent paper Green Against Greed: Negating Economic Capital Through Ecological Distinction, published in The British Journal of Sociology, I provide a detailed mapping of environmental views in social space. Generally, all kinds of environmental concern, engagement, interest and commitment is much more widespread among those with cultural capital on the left side of the social space. Through this, I challenge three kinds of explanations offered in the literature.

One is the prosperity thesis, which argues that once people are materially secure, they can afford to care about non-material issues like the environment. A second line of thought sees environmentalism as a form of symbolic distinction—something the privileged use to signal moral superiority and draw boundaries between themselves and people below them in social space. A third, more hopeful interpretation suggests that a new ecological habitus has emerged, particularly among those rich in cultural capital, such that care for the environment is now deeply ingrained in their dispositions and way of being.

However, I argue that strong ecological commitments among culturally privileged groups reflect the same logic that underpins their cultural tastes as well as their politics: a distancing from, rejection or even negation of economic capital and its various symbolic expressions. In culture, we see this as an embrace of interests and pursuits that value refinement, knowledge and new experiences, as opposed to luxury and ostentatiousness. In politics, we see it as an endorsement of left-wing politics that would rein in the power of economic capital. My contention is that the pro-environmental views of these groups are not simply about having enough money to care, nor are they just instruments for standing out from the masses, or the expression of a deeply transformed habitus. Rather, they reflect a long-standing disposition among high-cultural-capital groups to distance themselves from wealth, money, and materialism—values they associate with vulgarity, superficiality, and lack of seriousness.

This is not to suggest that individuals are consciously using environmental views to signal status or superiority. Rather, the argument is that for those relatively richest in in cultural capital, these stances make sense—they resonate with deeper dispositions. Rather than an argument about why, subjectively, individuals adopt the positions they do, my argument is more about why that position may appeal to these groups in particular.

For these analyses, I use data from the 2023–2024 wave of Norsk Monitor, a large and unusually rich national survey. I construct a model of the social space using Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA), where individuals are positioned according to their volume and composition of capital—economic and cultural. I then locate 26 different environmental attitudes and behaviours in that space. What I find is that pro-environmental views are systematically and strongly associated with groups relatively richest in cultural capital, and only weakly or inconsistently with groups rich in economic capital. If theories of prosperity, or perhaps even postmaterialism, were correct, we shouldn’t find this division within the dominant class, and the most pecuniary affluent should display a much stronger environmental engagement.

This environmental engagement shows a strong alignment with cultural tastes that are both resource-intensive and cultured: like listening to classical music, modern jazz or world music; interest in reading the culture section of newspapers; choosing to spend an unexpected day off reading a book; interest in vegetarian food; preference for interrail/backpacking holidays; and consumption of Moroccan cuisine.

These cultural tastes stand in opposition the lifestyles of those rich in economic capital, as well as the lifestyles of groups lower in social space, as we show in this paper., I refer to this as a form of symbolic asceticism—a valorising of scholastic, cultural and cosmopolitan pursuits, and a moralized distancing from material excess and economic power. In regression analyses, I show that this configuration of taste is not simply closely associated with pro-green views but actually accounts for much of the statistical relationship between social position and pro-environmental attitudes. Once these tastes are controlled for, the class effect is heavily reduced.

This also raises doubts about the idea of an ecological habitus. If such a habitus existed, we would expect pro-environmental views to be consistent, widespread, and deeply rooted. But the data show that these views are uneven and selective—even among the culturally privileged. Many express concern, but few prioritize the environment politically or join environmental organizations. Rather than a transformed habitus, what we are seeing seems to be a reworking of older symbolic oppositions, refracted through the lens of environmental politics.

The reason this symbolic asceticism takes the form of some degree of ecological orientation is, I propose, that the context has changed. There is now a heightened general awareness of environmental problems, and environmental issues have become increasingly individualized—both in terms of responsibility and expression. As Jean-Baptiste Comby has shown, this decisively pulls the environmental question closer to the home turf of those rich in cultural capital. Once framed as a matter of personal lifestyle, everyday choices, and moralized consumption, ecological engagement becomes a terrain where distinctions can be drawn through refined sensibilities, informed decision-making, and visible self-restraint—all of which align closely with the dispositions and resources characteristic of cultural capital. Through green marketing and greenwashing, ecological concerns have been commodified and made into lifestyle markers, which dovetails with the tendency of cultural capital groups toward stylization of life and symbolic mastery.

This takes place in a broader context where cultural capital has arguably become weaker as a basis for social power, not least because of rising economic inequality benefitting the wealthiest and various neoliberal reforms that have eroded its autonomy—particularly by reshaping the institutional conditions under which expertise can be mobilized and legitimized. In this setting, ecological concern becomes a way to reclaim moral and symbolic authority—an arena where cultural capital can still perform distinction and affirm its relevance by aligning with universalist values and the public good, while implicitly countering the logics of accumulation and economic instrumentalism. Against this backdrop, ecological engagement becomes a particularly potent way of negating economic capital. It allows those rich in cultural capital to assert a form of superiority not based on material wealth, but on taste, restraint, and moral awareness. Sighard Neckel has pointed out that the pro-green orientation fuses the three criteria of symbolic boundary work identified by Michèle Lamont: cultural (expertise on sustainability), economic (the means to afford green alternatives), and moral (claims to ethical superiority). In doing so, it offers a particularly effective way for cultural capital holders to legitimize their position—through lifestyle choices that appear at once rational, tasteful, and morally commendable.

The paper ends by arguing that this symbolic opposition to economic capital—expressed through cultural taste and ecological commitment—helps explain the distinctive green politics of the cultural-capital rich. Their environmentalism is part of a broader sensibility, one that values restraint, seriousness, and intellectual engagement over wealth, consumption, and convenience. In this sense, pro-environmental attitudes are not just moral or political statements; they are social position-takings in the fullest sense of the word.

Leave a comment